LA is decentralized, sprawling; but we can’t blame city planners of days gone by for our horizontal growth pattern. The desire to have our own little plots of sun-drenched land continues to trump the fact that vertical expansion would be a far better choice. This penchant for urban spread makes it difficult to have a cohesive viewpoint of Los Angeles, much less determine one iconic skyline. How is it possible to map such a mass?

Susan Logoreci makes intensely engaging and subjective landscape drawings of the urban disaster that is Los Angeles. A Cal State Long Beach grad, she’s a Northern California native, but a transplant to its southern region over a decade ago. Although her biography spans California’s geography, Los Angeles is at the heart of her work and figures in most of her drawings. These color field, prismatic maps have less to do with navigation, however, than they do with elegiac poetry.

Logoreci’s solo public art project “The Dream Décor of Oblivion” (2011) is up through mid-October at LAX Airport. It is fittingly in the Terminal One baggage claim area that services Southwest, the airline that frequently flies all over California and provides excellent views of our sprawl from the air. Logoreci’s LAX work echoes these aerial views, consisting of two 30-foot long by 10-foot high digital mural panels of a view of Los Angeles from the sky. Made from scans of her intimate and charming pencil drawings, “Dream Décor” evokes the kind of free, illustrated maps given out in tourist destinations that are paid for by prominently drawn local businesses. But in this case, Logoreci is the tour guide. Instead of street detail Logoreci gives us negative space, creating the impression that the city is connected by or bathing in clean, milky, negative space rather than car-clogged black asphalt.

Logoreci thinks a lot about cities. Look at her blog (http://susanlogoreci.tumblr.com/); she is interested in urbanism in general, and obsessed with Los Angeles in particular. While the mural at LAX is impressive, the nuances of Logoreci’s thinking about the city come through in her smaller works, like those exhibited in her recent solo show at Cirrus Gallery. The title of the exhibition, “It’s Hard To Know Where You Stand, When You’re Standing In It,” cannily evokes the experience of being in Los Angeles; individual perspective is the most immediate, yet most difficult way to locate oneself within the city.

The works in this show are delightful. Playful, imaginative, they take personal liberties with the landscape that allude to the dissonance between institutional, monolithic maps and individual, idiosyncratic paths through the city. Like pages out of a personal atlas of Los Angeles, the drawings show us that landscapes don’t have to be monumental, all encompassing, or navigable to be interesting. In fact, the mundane vista, or the under-looked byway might be better. Take, for example, her Los Angeles Bridges (2011). The average visitor might not even know we have bridges. But Logoreci turns them into a roller coaster ride, marrying Magic Mountain with urban overpasses. Logoreci has brought LA’s bridges together for the public, girders like pennants waving in the smog-choked breeze.

There are other instances of the celebratory in Logoreci’s work. Even the buildings in Downtown Los Angeles (In The Thick Of It) (2010) or the items on a shelf in her 99-cent store in 99 Cents Super Market Collapse (2009) are composed like a view from a mesa looking over the Grand Canyon: the urban landscape figures as sublime beauty. But it may be wrong to invoke monumental landscapes in reference to Logoreci’s work, despite the fact she has now, with the LAX commission, arrived there. Even though Logoreci works with grand vistas, the landscape is inflected with her comic, personal perspective. Blocks of color stand in for detail in many of the works, giving a sense of individual perception (foggy, general, emotive) rather than photographic detail.

Some works don’t seem to map the experience of being in Los Angeles specifically. Phantasmagorgeous (2010) is the artwork most like something you would see through a child’s kaleidoscope. Disorienting, topsy-turvy angles and triangles don’t particularly evoke Los Angeles, seeming like Bangkok or even San Francisco landscapes. Including gouache, it’s not surprisingly the most painterly of all her drawings.

Hollywoodlandgrab (2010) has a pensive quality. The abstraction in the piece relates to the uncomfortable mix of urban sprawl punctuated by local perspective that is Los Angeles. Tiny grayish apartment block windows furnish the only real detail in the piece, sprinkled through the landscape like ants. Modernist in its slightly blocky composition, negative space rips through the work; wherever streets should be there is nothing but blank white empty space. Unlike the LAX commission, the negative space in Hollywoodlandgrab reads as a kind of negation, blocking out rather than flowing under and through the city.

Riot Hyatt (2010), like Hollywoodlandgrab, plays with formal modernist tropes like color-block and line. A dark Mondrian, punctured and deflating, it brings to mind the way buildings fared in Japan’s recent earthquake and tsunami, stained glass color-block windows washing away into the street. At Cirrus Gallery it was hung next to one of James Griffioen’s photographs of Detroit’s decaying urban mass, suggesting a dire warning. What exactly we are being warned against is not clear (the vulnerability of cities to economic desolation?), but the pairing brought out a somber note in Logoreci’s works. Underscored is the sense that although Logoreci celebrates Los Angeles, she is more interested in reveling in its awkwardness than glamour.

People complain about LA. It’s too big, too spread out; it takes forever to get anywhere. But not Susan Logoreci. She draws the city’s architecture in a fanciful, lyrical hodgepodge of geometry and color. Her Los Angeles is deflating, collapsing, deliquescing and falling apart. And yet the drawings do not seem to be a lament for this gritty, sunny, ridiculously laid-out city. Logoreci’s candy-colored kaleidoscope drawings are an ode to her own personal faulty and flawed but well-loved Los Angeles.

Filed under: art reviews, Drawing | Leave a Comment

Tags: Cirrus Gallery, Drawing, James Griffioen, Los Angeles, Susan Logoreci

THE LEAGUE OF IMAGINARY SCIENTISTS Self-described as being “like kids who get to build a fort,” members of the League of Imaginary Scientists inspire thought and demystify science by taking complex subjects like global climate change and using them in exercises promoting creativity and social responsibility. Really Real Estate™ playfully asks, “What will happen when the Earth is uninhabitable?” Their solution: moving to outer space or the bottom of the ocean, two areas that they propose as being better alternatives than a climate-compromised surface of the Earth. Supported by a pseudo-scientific promo video and a kit of DIY materials including stickers with beautifully drawn data graphs and a telescope that you can make at home to scout out your potential outer space home, their suggestion functions simultaneously as comic relief, in light of actual scientifically-based outer space and undersea colony proposals, and provocation to think about the dire consequences of global warming.

Like a league of superheroes, LIS members contribute to projects with their own areas of expertise. The league also draws on real scientists who are happy to collaborate because of the intellectual freedom offered by an art-world context. For The Earth’s Biological Clock, league scientists Dr. L. Hernandez Gomez, Dr. Gouldstein, Professor William T. Madmann, Dr. Stephan Schleidan and Professor JoJo Johansen are working additionally with an environmentalist, a synthetic biologist, a neurologist, a genomic researcher and a science exhibit designer. An offshoot of the Really Real Estate™ project, The Clock is described by league members as a kind of “sea monster” or a new life form that has adapted to thrive in our increasingly toxic environment, tracking climate conditions via interactive data uploading.

Take note and mark your calendars: NYC-based ApexArt recently awarded the LIS a $10,000 curatorial grant for a show called X, Y, Z and U that will debut at Outpost for Contemporary Art in June. Beating out more than 450 other proposals internationally, the show will feature “mapping projects by artists and scientists who combine field research with DIY tactics,” according to league scientist Dr. Gomez.

THE INSTITUTE FOR FIGURING The Institute For Figuring, whose mission is to explore the poetry and artistry inherent within science, is also interested in the under-sea environment, specifically, the Great Barrier Reef. The Hyperbolic Coral Reef takes the threat global warming poses to the Great Barrier Reef and makes that issue accessible through a worldwide collaborative crocheting project.

The Hyperbolic Coral Reef is the brainchild of the IFF’s co-founders, Christine and Margaret Wertheim, Australian twins who are respectively an artist and a science writer. Inspired by the work of Dr. Daina Taimina, who proved the existence of non-Euclidian geometry with her hyperbolic crochet, the project began as a call on the IFF’s Website. Interested crocheters were asked to create different parts of the coral reef using Dr. Taimina’s hyperbolic crocheting techniques. The resulting “corals” are displayed together in installations that are astonishing, not only for their beauty, but also for the sheer amount of labor represented by the collected specimens; one Reef, shown recently at Track 16 in Santa Monica, included contributions from more than 60 crocheters. In its fourth year, the project has expanded into various satellite reefs shown around the world, and will include an upcoming show at the Smithsonian. Wertheim notes that tending to the project has become a full-time curatorial job.

Interest in The Hyperbolic Coral Reef comes not just from the organized art world, but more importantly, from crocheters, whose enthusiasm for the project points to the feminist issues raised by its collaborative, craft-oriented structure. Dovetailing with the surging interest in critical craft practices, Wertheim sees one of the project’s unexpected outcomes as opening “a wormhole into an alternate universe of creative feminine energy,” and providing a hopeful indicator of possibilities for collective creativity.WHIMSY IS THE HOOK THAT DRAWS THE VIEWER INTO THE PROJECTS OF BOTH THE LEAGUE AND THE IFF, BUT THE SERIOUS QUESTIONS AND COLLABORATIVE POTENTIAL FOR ADDING TO OR BEING A PART OF THOSE SYSTEMS ARE WHAT MAKE THEM SO COMPELLING AND THOUGHT-PROVOKING. ■

Artillery Magazine May/June 2009

Filed under: art reviews, Feminism | Leave a Comment

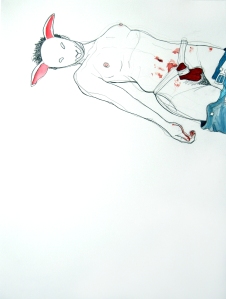

A few months ago, I had a show of drawings entitled “My Performance Anxiety” at Sam Lee Gallery. The drawings, simple line drawings of iconic feminist art performances, all shared the defining characteristic that in each I had obscured the artists’ faces, painting on animal masks in their stead. Although the animal masks are either formally or conceptually linked to the performance in question, for me their more important function was to hide or protect the artist’s face. My motivation for so doing came in part from my own personal mortification when confronted with performance art, and was both homage to and investigation of important feminist performance artists’ works. However, when asked, I wasn’t able to articulate a good reason for my anxiety on behalf of the artists themselves.

Two weeks later I read about the rape and murder of Pippa Bacca, and had sudden, painful clarity about the source of my fears. Bacca, a 33-year-old Italian performance artist, and her collaborator Silvia Morro, set out to hitchhike from Italy to Israel in an effort to promote peace in the Middle East. Calling their performance, “Spose in Viaggio” or “Brides on Tour” the women wore wedding gowns to symbolize their performance as a marriage between east and west. On March 31, a Turkish man named Murat Karatas picked up Bacca in Gebze, 40 miles outside of Istanbul. After driving her to a remote location, he raped her and, when she resisted, strangled her to death.

Some people fault Bacca for her own demise. After all, what was she doing, hitchhiking in a wedding dress by herself in Turkey? People had warned the two women to always stay together on their trip, had told them that Turkey in particular was not a safe place for women to travel alone. Newspaper accounts call Bacca “trusting” and “naïve,” implying that only someone who had a childishly simplistic view of the world would have undergone such a perilous journey. And I know that some of you are thinking that what happened to Pippa Bacca is terrible, but that really, it wouldn’t happen here. Egregious treatment of women in Muslim countries has made headline news in this country ever since the US began its public relations campaign against the Taliban. Who can ever forget the hidden-camera video of three women being stoned to death in a public stadium? That would never happen here.

But calling Pippa Bacca naïve for attempting to perform “Spose in Viaggio” smacks of the kind of blame-the-victim mentality that always holds women accountable the violence that men commit against them. And as far as thinking that this horrible event was isolated, and that it wouldn’t have happened in a western country, let me remind you that the statistics in this country on violence towards women are revolting. I don’t feel like I live in a terribly enlightened country when I read that every 15 seconds a woman is being battered in the United States. Or that one out of every six American women has been the victim of an attempted or completed rape in their lifetime.

Artists, like academics and critics, have usually been insulated from the risks that accompany real life, in that we can make work about something like rape, violence, death, or destruction, without risking actual exposure to those perils. The exception, illustrated with painful fatality by Pippa Bacca’s rape and murder, is performance art. Performance art done by women is particularly rife with dangers. Performance art is the marriage of the conceptual with the actual. It’s theory in practice. And this is why I think it is so threatening when women engage in performance art. It’s fine to believe in equality, but actually being confronted with “unfeminine” behavior is quite another thing.

The female body doing things it shouldn’t be doing (at least not in public, in front of people) activates both desire and repulsion- a dangerous combination. It’s confusing to mix opposites; it upsets the social order. The performance art of women like Pippa Bacca, Carolee Schneemann, Yoko Ono, Marina Abramovic, Ana Mendieta, Hannah Wilke, Martha Rosler, Kira O’Reilly, Mary Coble, Dawn Kasper, Chengyao He, Boryana D. Rossa, and Regina Jose Gallindo etc. etc. disrupts the boundaries between art and life. These artists took real risks with their art in order to make real change. Pippa Bacca is really dead because she was really raped and murdered.

None of this is new. Violence against women is old news. It’s nothing we haven’t heard before. But just because it’s an acknowledged truth, does that mean that we have to accept it? Just because it’s old news, does that mean that it’s not absolutely vital that people hear it again? No to smugly browbeat or dramatically breast-beat, but to try to raise awareness. Again. To try to incite change. Again.

We hear a lot about change these days, with it becoming such an over-used buzz word by both parties that it’s starting to mean its opposite. What we’ve seen in the presidential election is that when it comes to the politics of sexism, we are right back where we started, in spite of Hilary Clinton’s historic campaign. Vacuous right-wing eye candy in the place of a Vice Presidential candidate isn’t change: it’s Dan Quayle. The kind of change I’d like to see is a systemic paradigm shift away from gender inequality, sexism, and violence against women, and towards one where the work of artists like all of those named above would be of historical interest, but not of contemporary relevance.

I know it seems naïve and even ridiculously optimistic of me to think that could happen. But any radical change in social structure seems unthinkable until it’s happened. For example, if not for idealistic, optimistic activists, women wouldn’t have the right to vote in this country, much less run for president. The world has a long history of the ideal turning into the real. Anti-monarchists, suffragists, abolitionists, civil rights leaders, and all kinds of other revolutionaries were mocked and maligned in their time, too.

So I think that the next time I make work about feminist performance artists, rather than protectively hiding the artists’ faces, I should foreground them. Because the risks that these women take when they perform unfeminine acts deserve to be lauded, honored, and broadcast. I’ve realized that feminist performance art inspires not just anxiety, but a range of emotions including desire and repulsion, mirth and sorrow, shame and empowerment. The complications that feminist performance art evoke shouldn’t be obfuscated, but instead celebrated. When ideas turn into actions, the world can change.

Artillery Magazine Nov/Dec 2008

Filed under: Feminism, Performance Art, Pippa Bacca | 2 Comments

A couple months ago, after reading about Alan Kaprow’s New York show in Art in America, my husband and I got into a discussion about the validity of the happening as an art form and its relevance to current art practice. In sum, my husband cynically asked, “So if I brush my teeth and call it art, is it art?” Instead of taking the bait defensively, I decided to suspend the theoretical discussion and see if an experiential investigation might answer the question. If I understand it correctly, a happening is not concerned with a product but is instead a project. In other words, I was not going to get at what I wanted to know by going and seeing documentation of Kaprow’s work at MOCA. Instead, I needed to participate in a Happening.

My first attempt at so doing was to attend the informational meeting at Outpost on Robby Herbst’s re-creation of Household Revisited. However, I quickly decided that this happening was not for me. Instead of an experience, it seemed like an elaborate cross between improv, modern dance, and performance art. I was overwhelmed by the notes, instructions, and homework required to participate (come up with movements, arrive in costume, contemplate the meaning of ecological and humanistic perfection). Plus, nobody else was from Long Beach, so there was nobody to carpool with up to Lancaster.

I passed.

Somewhat discouraged that I wouldn’t be able to participate in a happening, I started thinking about doing one on my own. There are many to choose from, but the one I considered, as retold by Paul McCarthy in Art in America, March 2008, had to do with going to a thrift store, getting clothes, washing them at a laundry mat, and then returning the clothes to the thrift store. While pondering the ethical considerations involved in re-invention (Could I use my own washing machine? In today’s water and energy crisis landscape, would it be ethical to wash just one or two items? Would it compromise the legitimacy of the Happening if I included some of my own laundry in the cycle?), I heard about the re-creation of Kaprow’s Fluids happenings.

Fluids was first done in Los Angeles in 1967. Organized in conjunction with a show at the Pasadena Art Museum, the directions for Fluids were simple: “During three days, about twenty rectangular enclosures of ice blocks (measuring about 30 feet long, 10 wide and 8 high), are built throughout the city. Their walls are unbroken. They are left to melt.” In the 60’s Kaprow succeeded in producing thirteen of the twenty sites envisioned. In 2008, LACMA coordinated the Fluids events with an unusual and impressive display of inter-institution coordination and cooperation from the Getty, MOCA, LACMA, the folks at JPL, and various cultural and educational institutions and organizations. Union Ice provided the ice in 1967 and 2008. I committed to attending the Westchester Park Fluids, spearheaded by Otis’ Michele Jaquis and Jerri Allyn. I can’t do heavy lifting, so I took my camera and participated by documenting.

At this point in my narrative some of the Kaprow-purists among you might be fiercely objecting to a) me thinking that I was participating by taking pictures and b) the fact that I was taking pictures at all. Indeed, the two central arguments that I heard from critics of the reinventions of Kaprow’s happenings were the institutional involvement, and the rampant documentation. Kaprow was famously anti-institution and anti-documentation. Indeed, one student in Marlena Donohue’s Otis Kaprow course, for whom participation in the Happening was a mandatory class event, said she thought the Happening was “bullshit” because to be a real happening, it shouldn’t be institutionally sponsored or documented. Whether or not you agree with said student’s sentiments, her statements underscore the very un-avant gardeness of the place of the Happening in contemporary art. Seen in this light, one could interpret the LACMA/MOCA Kaprow celebration as a kind of memorial to the Happening rather than a revival thereof.

In my dual role of photographer and reporter, I was able to observe and interview the Fluids participants and the audience that gathered to watch them build the 30’x10’x8’ ice sculpture. On a scorching hot April day, park-goers were drawn to the giant mass of ice. I documented the participants and spectators, occasionally prodding members from either group with my query, ”But is it art?” Thinking my question would arouse controversy, I was surprised when people genially answered in the affirmative. Dog-walkers, little league moms, construction workers, and art-lovers were unanimous: “Yes, of course it was art!”

However, I soon realized the problem. There was confusion around the “it” to which I referred. Respondents all assumed that I was asking whether the structure itself, which looked like a modernist igloo, was art. To an audience used to public minimalist sculpture, the big, shiny white cube was recognizable as such. The problem with evaluating Fluids as a Happening was that in effect, participants became minimalist sculptors. Having been reassured that minimalist sculpture was art, I was still left with my initial conceit: was the happening itself art?

I can only answer by telling you what it felt like to participate. Fluids felt more like a Barn-raising than a play or performance. In part, this was due to the surprising number of people I know who took part in or helped organize Fluids recreations. Participating in Fluids gave me a sense of being part of a larger artistic community. It’s easy to feel dislocated in LA’s urban miasma, so it’s nice to feel like you’re a part of something. That community feeling extended to the Westchester site: participants were collegial, friendly, and focused on the task at hand.

When the structure was complete, the last block in place, there was a sense of collective pride in our accomplishment. I believe this is true for everyone who was present, from the Union Ice employees to the participants, to the documenters and spectators. I certainly felt a kind satisfaction at having participated in my own way. I could say something pithy here like, ”If that’s not art, it should be.” But that wouldn’t be right.

It did leave me thinking, “If the structure of the happening is to turn the fabric and materials of everyday life into art, what is the goal?” Again, my experience was that participating in a happening was like enacting a kind of conscious ritual. Like focusing on breathing, the happening isn’t about a product or an end game; it’s about an experience. Hence the title of Kaprow’s traveling retrospective: Art is Life. But not like brushing your teeth and ex-post-facto calling it art. More like taking the actions and materials of everyday life and slightly tweaking or de-contextualizing them so that the action is deliberate, considered, and purposeful.

Maybe the problem with evaluating the Happening on its own terms is that it has fed and informed so many other kinds of art. For example, after seeing the participants comparing red welts on their arms left by hours of carrying 50lb blocks of ice, I realized the Happening’s influence on endurance art. Robby Herbst’s dance/play in the desert has a similar air of endurance art, (or at least it seemed to me that cavorting for hours in the high-desert sun would end up being endurance art). Co-opted, diluted, expanded, and extended, the Happening is woven into the history and current practice of art and popular culture. From Performa to Flash Mobs, the idea of doing something, not making something as art is accepted artistic practice. Yes, it’s art. Of course it’s art. Because it is conceived of and executed as art. Because now that technique and craft and formalism are no longer the gatekeepers to art making, the art is in the idea, not the product. And that, in part, is Kaprow’s legacy.

I still have doubts about the validity of my happening experience. Partly this is because of all the hype surrounding Fluids, partly because of the institutional involvement. Also, since I didn’t carry the ice-blocks, was I really a part of the happening? So I have decided to go back to my penultimate idea: the thrift store piece. In the spirit of authentic happening, there will be no institutional involvement (LACMA will not sponsor my Happening) and there will be no documentation. I will follow Kaprow’s instructions. I will go to a thrift store. I will buy clothes. I will wash them, and then return them to the thrift store. There will be no audience, only me as participant.

And I will do a full load.

Carrie Yury

Los Angeles, May 21, 2008

Published in Artillery Magazine

volume 2 issue 6 july/august 2008

Filed under: art reviews | Leave a Comment

The Cool School, directed by Morgan Neville (2007, 86 minutes), documents the genesis of the LA art scene from the late 1950’s to the late 1960’s by telling the story of Los Angeles’ Ferus Gallery. Following the development of Walter Hopps’ initially inclusive, expansive vision for Ferus Gallery to its eventual sculpting into an exclusive, cosmopolitan business by later partner Irving Blum, we are introduced to many of the gallery’s key players and given access, through present-day interviews, to their stories. The film’s title seems to refer to its thesis: that the Ferus Gallery entourage literally schooled Los Angeles in the development of cool, teaching it how to act like a city that had an independent, sophisticated, and art-focused cultural center. We are instructed in the view that the Ferus Gallery served as the catalyst that helped catapult Los Angeles’ cultural development from a conservative backwater to a city with a world-class art scene.

The Cool School follows the Ferus Gallery director/owners Walter Hopps and Irving Blum from the gallery’s inception to its bitter end. In the beginning, Walter Hopps worked with an indiscriminate number of artists from San Francisco and Los Angeles. Irving Blum’s partnership focused the gallery, cutting out the San Franciscans, and representing, at least for a time, only a select set of LA artists. That core set of male artists was Ed Keinholz, Ed Ruscha, Ed Moses, Larry Bell, Ken Price, Billy Al Bengston, Craig Kauffman, John Altoon, Robert Irwin, and briefly but notably, Wallace Berman. We learn what it was like to be part of the cool school through the descriptions and artifacts of the artists themselves. Narrated in hard-boiled voice-over by Jeff Bridges, The Cool School combines vintage photographs, period newsreels, and archived interviews with present-day interviews. Although perplexingly rendered in black and white, the present-day interviews give the film its real meat, offering up perspectives on history from key artists, collectors, gallery owners, and critics who were Ferus Gallery insiders, with some additional counterpoint from a few outsiders. Indeed, the theme of insiders and outsiders recurs throughout the retelling of Ferus, as a picture quickly develops of the core Ferus artists as a clique-y, competitive group of men who were as famous for their macho antics and bad-boy posturing as they were for their abstract expressionism, assemblage, and innovative use of materials.

The outsiders’ perspectives provide useful contrast to the enthusiasm of the Ferus insiders. For example, the film is punctuated by the crankily acerbic perspective of NY art dealer Ivan Karp, who, as the voice of New York, has nothing but nasty things to say about LA’s museums, galleries, and collectors, its artists, their media, and its art scene in general! His unilateral distaste for everything LA does a good job of validating one of the film’s central theses: that by staying in LA and shunning New York the Ferus artists were rebelling, perhaps dangerously, against the established art market.

Though they may have been rebels, they were not activists seeking social change. They were modernists trying to express individual artistic visions and to gain personal fame and glory. Nowhere is this more clearly evident than in the film’s examination of women’s place in the Ferus Gallery. We hear from Sonia Gechtoff, one of the San Franciscans who was excluded from the gallery once Blum came on board. One of the few women interviewed, her part in the film is brief but memorable. A cutting-edge abstract artist, Gechtoff’s short history with the gallery underscores the lack of recognition, and deliberate exclusion of women from Ferus. In sum, Shirley Nielsen Hopps, the ex-wife of both Hopps and Blum, says, “They serviced the men. That’s what the women did. Simple as that. They put up with it. They cheered, cried, (and) they’d cook.” Nielsen Hopps’ comments make it clear that while Ferus was in its heyday, women were relegated to purely supporting roles. However, the film makes a connection between the fact that the Gallery’s exclusionary practices ultimately contributed to its demise, citing the sea change in the art world in 1968 characterized by a move away from elitist male-centric modernism and towards “the beginning of feminism and democracy in the arts.”

The Cool School is educational, providing an interesting perspective on the development of LA’s art scene. However, for a film about a critical period in the development of art, many of the stylistic choices seem arbitrary, such as heavy use of fake film crackle, or the punctuation of black and white scenes with red, like a cigarette butt’s red ember against an otherwise colorless field. Indeed, many of the aesthetic choices seem to distract from the film, rather than add to it. Also, the film seems a bit loose structurally, and could use a tighter focus for greater cohesion, as timelines and storylines are sometimes confusing.

The film ends with Ed Moses lamenting that Walter Hopps never got around to writing down his memoirs. According to Moses, this is a great loss because only Hopps knew the real story, and without his memoir, the record will be lost. Moses complains that now, “the record is going to be interpreted, rather than defined. That’s the problem with critics and everybody, they think they have to interpret what’s going on- all they have to do is see it!” But history is really the art of interpretation, as is borne out by the artists’ different versions of history. For example at the 2004 reunion of surviving members there are divergent opinions about which of them blackballed de Kooning’s bid for entry into the gallery. History, or the truth is different depending on who is telling the story.

The film walks a complex line between lauding the genius of the Ferus project, and pointing out its failings. On the whole “The Cool School” seems to err on the side of romanticizing the mythos of Ferus. However, the film’s grand commingling of the art, the relationships, the gossipy scandal, the personal tragedy, and the business practices of the Ferus Gallery, set against the background of LA’s burgeoning cultural development makes for entertaining, if slightly peripatetic viewing.

Published in Artillery Magazine, March/April 2008

Filed under: Film Reviews | Leave a Comment

Tags: Ferus Gallery, Los Angeles

Pipo Nguyen-duy, East of Eden

Sam Lee Gallery, Chinatown

Pipo Nguyen-duy’s “East of Eden” at Sam Lee Gallery is an exhibition of beautiful, large-format, staged color photographs that manage to be lyrical, sentimental, conceptual and narrative, all at the same time. A self-confessed response to the loss and rebirth of America’s Edenic status in the post-9/11 imagination, East of Eden is Nguyen-duy’s attempt to explore and rebuild the mythos of American exceptionalism. Taking his historical cues from the Hudson River Valley School’s use of the landscape to explore ideas of nationalism and optimism, Nguyen-duy presents us with landscapes that play out some of the fears, anxieties, and grief in our orange-alert consciousness.

Nguyen-duy’s theatrical scenes are firmly fixed in the tradition of staged photography. Their aim is not to reinvent or question the medium, but rather to use its narrative potential to tell us the kind of stories that we need to hear. The photographs hit home because they point out something that we already know, crystallizing our more obvious fears (like terrorists in the grass, or a child witnessing an explosion at the end of the earth), but also pointing to the possibility of a path of mourning and moving on.

East of Eden presents an assortment of images on terrorism, the traumatic and the everyday. These staged photographs do not attempt to mimic reality, choosing instead to dwell in the theatrical world of make-believe. “Mountain Fire” evokes every disaster movie Hollywood has ever produced. “Pumpkin Field” and “Lazy Boy” are achingly beautiful landscapes that bring to mind the nature-as-enemy genre of horror films (there’s something evil in that water/pumpkin field/forest). But not all of the photographs are filmic; in fact most have painterly composition. For example, in “Marching Band,” a dozen bedraggled marching band members sit on the edge of a riverbank. Rather than marching, or even playing their instruments, they sit in somber contemplation, never more isolated than when in a crowd.

“Swordsmen” and “Walk Home” seem emblematic of the work’s themes. In “Swordsmen,” a group of white-clad, masked fencers thrust, parry, fall, and help each other up in a snow-covered wood. They fight, but in a controlled way, with rules. It’s a fantasy of benign, regulated aggression that I appreciate, one that is so laughably the opposite of the terror to which “East of Eden” responds, that I can only see it as a tongue-in-cheek, self-aware longing for a world where differences are settled in plain sight, according to a common set of rules, and with sportsman-like camaraderie. “Walk Home” is both an ending and a beginning, the proverbial walk of shame home after a one-night-stand, still clad in last night’s party clothes. There is shame here, but also hope, anticipation, and excitement at the effulgent possibilities in the day ahead. Optimism in the face of ignominy, the desire for order and honor instead of chaos and disorder-Nguyen-duy presents a fantasy for us that is not quite, but just east of paradise.

Published in Artillery Magazine Fall 2008

Filed under: art reviews, photography, sentimental conceptualism | Leave a Comment

Tags: photography, Pipo nguyen-duy, sentimental conceptualism

“There’s a poet says his favorite place on earth is Italy, cause that’s the only country where men weep openly. Well I ain’t never been there, but I’ll go before I die, and I’ll walk though the piazza watchin’ people watch me cry.”

From “I Cry Easy,” Brett Eugene Ralph’s Kentucky Chrome Revue

Shortly after I first became acquainted with the odyssey that is Brett Eugene Ralph’s Kentucky Chrome Revue, a male friend of mine asked me how I felt about the album. When I gushed about how much I loved it he replied, “Must be a chick thing. All the women I know feel the same way”. While I have since talked to many men who are great fans of Revue, the idea that there was some sort of gender divide in response to the album puzzled me.

What I think my friend might have been referring to has to do with emotion. In my view, the appeal of Brett Eugene Ralph’s Kentucky Chrome Revue is its frank, bare expression of feelings. An album of let downs, breakdowns, and inadequacies, Revue does what music does best; it makes you feel. Ralph is not ashamed of and indeed he delights in an exhibitionistic display of emotion. There is no cynicism, no theory, no critical distance. Revue unabashedly revels in a straightforward, balls-out, heart-on-sleeve emotional wallowing, parading his shame, gut hanging out. The album’s strength is its description of weakness and vulnerability. An apt metaphor for the album as a whole, the “Chrome” in the album’s title refers to Duct Tape, the poor man’s silver. Like the character in “I Cry Easy,” Ralph takes pride in exhibiting his soft spots, which is not something men in this country are encouraged to do.

Though the lyrics and tone of the album revel in weakness, the outrageous all-star cast of the Revue contains some of Kentucky’s most illustrious contemporary musicians, among them Catherine Irwin, Will Oldham, and Wink O’Bannon. Rather than being overwhelmed by all the stars, Ralph is supported by them. A prime example of this is Freakwater’s Catherine Irwin, who sings most songs with Ralph, either in duet or in backing vocals. Irwin’s voice is a superb, mellifluous instrument, but rather than drowning out Ralph, the two work in perfect counterpoint to one another. Ralph’s voice is yet another example of the theme of strength through weakness. Rather flat and nasal, by all rights it shouldn’t work, and yet it does because of the fallibility, vulnerability, and authenticity that it embodies.

For all the emotion it contains, Brett Eugene Ralph’s Kentucky Chrome Revue is no downer. “I Cry Easy” is practically a rousing sing-along, a jubilant choir belting out the chorus along with Ralph. The most bittersweet of songs, “Happened to Be,” which describes a violent, drug-addled, abortion-strewn relationship, still manages a sweetness of melody and instrumentation that produces the kind of pain that feels good. Earnest though it may be, Revue also has moments of self-conscious humor, as in Ralph’s version of Iggy Pop’s classic “Your Pretty Face Is Going to Hell” in which, after an impassioned plea for love, the singer reminds the listener that everyone’s looks will eventually go to hell.

The irony of women loving the album is that Ralph’s representations of women run from the unflattering to the misogynist. As revealed in songs like “Women Always Do,” the narrator’s view of women is often compromised by the dysfunctional relationships he has with them. The album is populated by extreme stereotypes such as prostitutes with hearts of gold, cheating women, or self-destructive and abused girls. Nonetheless, the fact that the men in Revue are equally damaged takes the sting out of his representations of women. Drifters, emotionally stunted men, and addicts complete the cast of characters.

However, Ralph is not interested in simply representing stereotypes of the poor south. If anything, Brett Eugene Ralph’s Kentucky Chrome Revue is an attempt to come to terms with and even rejoice in the abject heritage of the rural indigent. For example, “Grandpa Was A Hobo” simultaneously paints a picture of the mantle of masculinity that forbids men from admitting weakness, and of a young son struggling against those injunctions and taking pride in his ignominious lineage. Altogether, Ralph creates an album that is both lament for and celebration of the characters that populate his Kentucky.

June 14, 2007

Filed under: Music Reviews | 1 Comment

Tags: Brett Eugene Ralph, Kentucky Chrome, Men and Affect

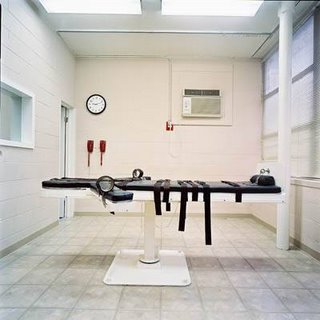

Richard Ross’ Architecture of Authority at ACME is a series of photographs of architecture that is active, aggressive, built for a specific, state-sanctioned violence. Interrogation room, interview room, pat down room, booking bench, holding cell, and lethal injection room, the lesson here is end-game- the state has made you, and it can literally unmake you, stripping your rights, your individuality, your freedom, and your life.

The photographs are hung in restrained salon-style groupings of up to four images that relate to one another. Though comprised of individual works, the groupings make sense, forcing us to see the similarity of spaces, the replication of authority’s tactics relative to a specific goal. For example, the hallmark of the interrogation room is a single chair, though the accessory in Santa Barbara is a roll of toilet paper to stem tears and runny noses, while in Guantanamo it’s handcuffs that attach to the floor. Minimalist and almost monochromatic, the photographs are devoid of the bodies, emotions, and actions for which the rooms were built. Stark, crisp photographs that show every detail in the frame, the punctum in the images is their relentless referencing of human bodies, and yet their refusal to show us any. But the bodies are there like ghosts, populating the empty images. We imagine the people who have sat in the interrogation chairs, or on the booking bench. We feel the guard’s uneasy authority in the lethal injection room, ineffective air-conditioner blasting on the back of his neck.

It’s difficult to choose the most chilling, but for me it’s the segregation cells at Camp Remembrance, the new Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Open to the elements, the cells simultaneously expose and imprison the prisoners. These flimsy structures seem to say everything about the administration’s justification for holding the prisoners in the first place, underscoring the inequity of our war on Iraq.

In the East gallery, most of the photographs are from television police procedurals like Law and Order, and NYPD Blue. Showing our cultural fascination with a fictionalized version of the moment of interrogation, of getting to the truth, these photographs comment on our glamorization of what is ultimately an intensely unglamorous architecture. Two real interrogation rooms are set in this gallery. Smaller photographs, they seem squeezed onto a smaller wall, like afterthoughts that can’t compete with our fantasy of interrogation.

Architecture of Authority is about the spaces that enable the excesses of authority. Ross’ point seems to be not that architecture forces us to behave in certain ways, but rather that without collusive, willing ambassadors of the state, architecture is powerless. Architecture of Authority shows us that without the guard, the bureaucrat, the official, and the prisoner, there is no apparatus of authority, just a bunch of empty rooms.

Summer 2007

Filed under: art reviews, photography | 1 Comment

Tags: Althusser, Architecture, Authority, Interpellation, Richard Ross, violence of complicity

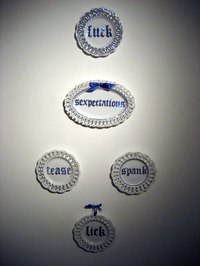

Mindy Cherri “Sexpectations”

The Office, Huntington Beach, CA

Feb 24- March 23, 2007

My mother has a decorative plate collection that hangs in the dining room. State plates proclaiming “Montana, the Big Sky State!” mingle with delicate blue Dutch Delft dishes. At first blush, the china plates in Mindy Cherri’s “Sexpectations” at The Office in Huntington Beach mirror my mother’s collection. White plates with blue lettering are cozily hung salon-style on blue ribbons, domestic Americana transported to the gallery. However, it quickly becomes clear that the pretty plates are not just good clean kitsch. They’re actually quite dirty. And I mean dirty the way your mother would, the kind of dirty that, in my early days, would make my mother threaten to wash my mouth out with soap.

Mindy Cherri’s “Sexpectations” is comprised of an assortment of delicate white china plates, each emblazoned with its own dirty word. Cherri painstakingly creates the sparkly Old English calligraphy on the plates by placing scores of crystals with a dental tool, going back in later to excise any remaining glue and to polish her dirty words to an azure brilliance. “Beaver” “Pussy” “Dickalicious” “Slut” are among the dirty words that erupt on the plates.

Thinking about the exhibit brings to mind another of my mother’s exhortations to “clean your plate”, and makes me wonder, what does it mean to have an embellished hanging plate scream “Beaver” at you? I think that Cherri’s plates represent a return of the repressed, an attempt to show how the things we want to hide (or hide from) come back, not so much to haunt us as to tease us, to poke fun at our prudishness. Rather than exemplars of mid-American domesticity, these plates are an uncomfortable reminder of the funny, messy, dirty body, that-which-domesticity-tries-to-contain. Cherri’s plates serve up delicious contradictions, putting that-which-should-be-hidden on display.

Cherri buys china pieces ready-made from a company that sells mostly to people who hand-paint china. The upper-class-aspirational, society past-time of hand painting china invokes visions of ladies of leisure, Junior League members who train future generations of young ladies in suitable manners, protocols, and behaviors. That Cherri’s plates are not at all suitable is part of the joke.

Like someone gone crazy with a Bedazzler“‰, Cherri puts her own salacious spin on the kitsch memento. An in-your-face re-appropriation of craft, a re-imagining of the readymade, Cherri’s sculptures meld the modernist simplicity of Duchamp’s urinal with the kind of elaboration and embellishment that still signify “beauty” in pop culture America. In so doing, Cherri takes the piss out of the public, the masculine, and minimalist modernity, instead serving up the domestic, the kitsch, the feminine, and embellishment. “Sexpectations” is deliberately quaint, decidedly funny, and quietly disruptive.

Filed under: art reviews | Leave a Comment

Tags: Dirty Words, Mindy Cherri, The Office

Echoes

“Echoes: Women Inspired by Nature” at the Orange County Center for Contemporary Art

Santa Ana, CA

May 8, 2007

“Echoes: Women Inspired by Nature” at the Orange County Center for Contemporary Art complements the national re-investigation of feminist art work spearheaded by the WACK show at MOCA. Curated by Betty Ann Brown and Linda Vallejo to focus on women who have been inspired by nature, “Echoes” brings together an eclectic group of nature-inspired work, ranging from celebrations of mother nature in her glory to apocalyptic notes on her decline. Call me a cynic, but I found the work the most interesting on this latter end of the spectrum. In fact, I would say that this sub-category work is not so much “Inspired by Nature” as it is inspired by the unnatural, particularly with respect to man’s effect on the environment.

Take for instance Kim Abeles’ “Presidential Commemorative Smog Plates”. In the early 1990’s, at a time when global warming was commonly regarded as a kind of hoax orchestrated by left-wing radicals, Kim Abeles was quietly creating art using LA city smog. Abeles placed stencil cut-outs of U.S. presidents’ faces on china plates, and them left them on her rooftop, letting the smog do its work. Combined with piercing quotes from each president that reflect their administrations’ impact on the environment, Abeles’ work is even more trenchant and timely in 2007 than it was 14 years ago. A brilliant piece of political, environmental work, Abeles’ work should be on permanent display in a major U.S. venue.

Another artist in the show whose work is inspired by the unnatural effect man has on nature is Yaya Chou. Her two pieces “Joy Coated” and “Chandelier” are both sculptures that go past the merely unnatural and into the synthetic. “Joy Coated” is more didactic, a child-size mannequin coated in Gummi Bears that melt at the child/doll’s extremities, having/becoming the jouissance of childhood obsession: candy. The highly saturated, surreal colors of the Gummi Bears underscore this sense of humor and unease, evoking our nation of obese children, poisoned by toxic, synthetic food. “Chandelier” is a more subtle variation on the theme. Also made from Gummi Bears, it emits not only an eerie amber light but also an attractive/repugnant smell of dusty, hot, gelatinous High Fructose corn syrup, akin more to the nauseating sweetness of bug spray than to the enticing aroma of butter cream frosting.

There are other notable examples of the unnatural in the show, including Linda Frost’s creepy “The Tortured Souls” series, digitally manipulated photographs commenting on the use of animals in testing, and Pamela Grau Twena’s “Protecting the Seeds”, a circle of bronze cast barbed apples that warn of the consequences of man messing with nature. Set in a circle protecting a few dessicated grapes, Twena’s thorny apples evoke other fabled apples (Eve’s, Helen’s, Snow White’s). Except in this case it is not just woman who is punished for her transgression, but rather all mankind if our machinations with bio-agriculture produce the kind of monstrous fruit that Twena imagines.

Samantha Fields’ “In the Belly of the Beast” is the most apocalyptic of the group, and also the one that brings us from a meditation on man’s unnatural effects on the environment to nature’s infernal responses thereto. Depicting the hills of LA on fire, her somber acrylic painting is both a vision of hell and a warning. The LA area chapparal needs fire as part of its cycle of growth, but sprawling over-development combined with global warming’s drought and flood pattern redistribution make it so that fire is increasingly lethal. Fields’ piece seems to say that nature will have the last word, even if it means the end of us.

Published in Artillery Magazine

Filed under: art reviews | Leave a Comment

Tags: art review, feminist art work, occca

You must be logged in to post a comment.